Whenever I enjoy anything in art it means that it is mighty poor. The private knowledge of this fact has saved me from going to pieces with enthusiasm in front of many and many a chromo.

—Mark Twain, 1891

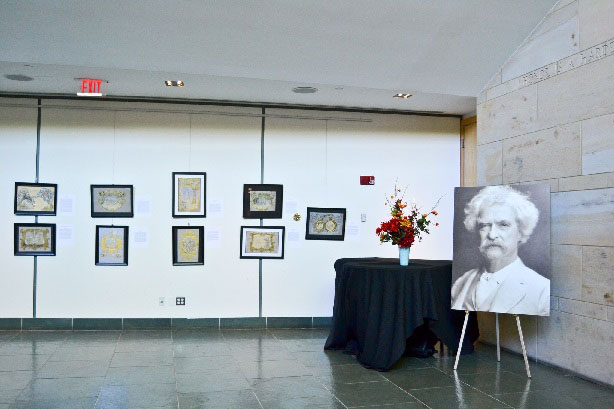

Fortunately, Mark Twain’s art knowledge does not dominate our museum, which is currently exhibiting works produced by Middle and High School students in drawing classes at Hartford Magnet Trinity College Academy (HMTCA), led by Ms. Stephanie Munzi and Mr. David Davies, respectively. And while their work did not use the complicated printmaking technique of chromolithography to which Twain referred, it is no less powerful. We hope the thousands of visitors who pass through The Mark Twain House & Museum each summer will, in fact, go to pieces in front of the drawings.

Each year, students at HMTCA’s drawing classes produce both art and essays which respond to the themes of our special exhibit. This year the exhibit is In Their Father’s Image: Susy, Clara, and Jean Clemens, which explores the lives of Samuel Clemens’ three daughters. I visited the middle school classes in the Spring, prompting the students to compare their lives in 21st century Hartford to the Clemens daughters in the 19th century. We discussed the city’s position and importance at the, their own sense of cultural identity in comparison the Clemens daughters’, and their own education vs the Clemens daughters (Susy, Clara, and Jean were mostly taught by governesses at home, with stints of public school). Good history captures the human experience, not dry dates—it is a way of exploring what it felt like to be in a different period of time, and comparing the lives of girls in the same city across the centuries captured that poignantly.

The High School students took a different route: we recreated a storytelling game played by Samuel, Susy, Clara, and Jean Clemens, where Sam had to tell a story using all the objects on the family’s library mantle as characters. He had to go in the same order each night, but compose a different story each time. Similarly, the students wove a story collaboratively, using objects in the museum’s collection, and illustrated their own portions of the tale. Working collectively to build a story was a lot like improvisational theatre.

Art was important to Twain’s work when first published, in ways not often understood or embraced today. Most editions of his novels in print at the moment are not illustrated, despite their first editions being replete with images. Indeed, Twain himself picked illustrators and supervised the eventual illustrations, for which see Stephen Railton’s wonderful discussion of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Twain wanted his words illustrated, took the pictures seriously, and exerted authorial control. It is fitting, then, that we use art to illustrate his words and his daughters’ lives.

By James Golden

Director of Education

The Mark Twain House & Museum