Welcome to Sam’s Shorts! Each month we bring you a brief passage from one of Mark Twain’s less-familiar works, inviting you to read, reflect, and respond. Then we share what we learned from your responses, answer some of your questions, and tell you a bit more about the background and context of the piece. You can read the current Sam’s Shorts selection here.

In spring 2021 we read selections from a piece by Clemens titled “A Curious Pleasure Excursion,” published July 6, 1874 in the New York Herald.

Reader reflections

This piece made many readers think of the famous connection between Sam Clemens and comets: he was born in 1835, a few months after Halley’s Comet appeared in the skies, and died in 1910, the year it next returned.

In addition to wondering how Clemens himself and 19th century Americans more broadly thought about space and the unknown, readers really noticed the centrality of colonialism–and Clemens’ critique of it–in this piece.

This passage made me think about both the wonder of space and the unknown, juxtaposed with American Imperialism and foreign policy in the 1870s, where the idea of encountering Alien life is built around converting them with missionaries and intimidation rather than wonder.

It made me think that Twain’s ribbing of Missionaries began decades earlier than I had thought.

Religion in space

This also reflected in the line that readers were most drawn to: “We shall take with us, free of charge A GREAT FORCE OF MISSIONARIES and shed the true light upon all the celestial orbs which physically aglow, are yet morally in darkness.”

Sam Clemens and Space

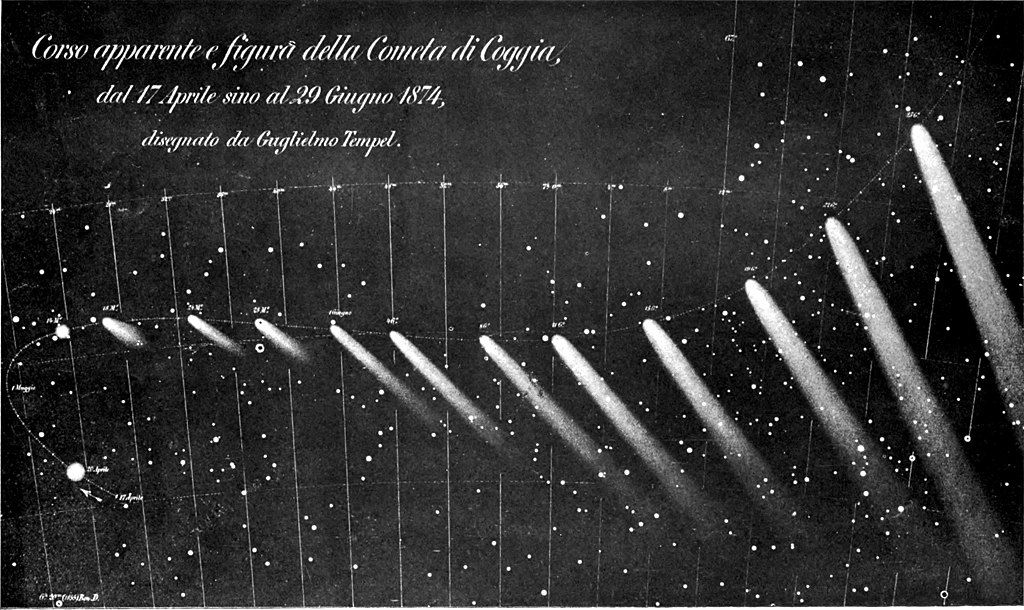

In April 1874, astronomer Jérôme Eugène Coggia discovered a comet at the Marseille Observatory. Known as Coggia’s comet, or the Great Comet of 1874, it was visible to the naked eye by June. It caused quite a stir, and even a panic among some–but for Sam, it was inspiration to poke fun.

Sam himself seems to have been fascinated with the mysteries of deep space and inclined to draw on it in his writing, as we’ve seen in previous shorts. Readers’ favorite line from his 1871 Christmas letter, after all, was “that diminishing milky-way of white wings.” A few Christmases later, he wrote as Santa Claus to his daughter Susy, listing Santa’s home as “the Palace of St. Nicholas, In the Moon,” even noting that Santa was sometimes known as “The Man in the Moon.” We can’t find any other mentions of this connection in the historical record, so perhaps it was a family tradition–let us know if you’ve ever heard of this!

He was simultaneously interested in deep time as well–after all, our very first short dealt with Adam & Eve and dinosaurs. In a letter to his fiancée a month before their marriage, Sam shared some of what he’d been reading and how it was making him think about the connections between deep time and deep space

I have been reading some new arguments to prove that the world is very old, & that the six days of creation were six immensely long periods. For instance, according to Genesis, the stars were made when the world was, yet this writer mentions the significant fact that there are stars within reach of our telescopes whose light requires 50,000 years to traverse the wastes of space & come to our earth. And so, if we made a tour through space ourselves, might we not, in some remote era of the future, meet & greet the first lagging rays of stars that started on their weary visit to us a million years ago?—rays that are outcast & homeless, now, their parent stars crumbled to nothingness & swept from the firmament five hundred thousand years after these journeying rays departed—stars whose peoples lived their little lives, & laughed & wept, hoped & feared, sinned & perished, bewildering ages since these vagrant twinklings went wandering through the solemn solitudes of space?

How insignificant we are, with our pigmy little world! . . . Does one apple in a vast orchard think as much of itself as we do?—or one leaf in the forest,—or one grain of sand upon the sea shore?

Both of these things–the geologic age of the Earth and the mysteries of space–captivated 19th century Americans of all stripes, and Sam was far from the first to draw on these wonders for creative and conversational purposes.

1835, the year of Clemens’ birth and Halley’s arrival, was a good one for space travel writing. In June of that year, Edgar Allen Poe’s short story “Hans Pfall–A Tale” appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger. In it, the title character journeys to the Moon by balloon, aided by an “apparatus for the condensation of atmospheric air.”

Poe’s story was quickly overshadowed by the late summer publication of a series of six articles in the Edinburgh Courant which would come to be known as the Great Moon Hoax. These articles, supposedly written by the contemporary English astronomer Sir John Herschel, detailed the discovery of life on the moon “by means of a telescope of vast dimensions and an entirely new principle.” Not only did these articles claim the presence of birds and herds of animals on the moon, but also the identification of “Vespertilio-homo, or man-bat,” witnessed through the telescope by “civil and military authorities of the colony, and . . . several Episcopal, Wesleyan, and other ministers.”

Moon travel stories were popular, especially given the ballooning craze, but comet travel appeared in 19th century fiction as well. One story that mixed the two was 1835’s “Glimpses of Other Worlds” by Thomas Charles Morgan, which recounts explorations on the moon as well as a trip on a comet whose direction and speed were altered “with the aid of a phial or two of concentrated essence of gravitation.”

Despite this and the other technological marvels that feature in these stories–telescopes, balloons, and atmospheric air condensers–Gilded Age folks knew that much was still unknown about the space beyond their own atmosphere. As an 1891 article in the Nehema County Republican (KS) queried: “OUTER SPACE. Is it air–or What–Where the Great Stars Shine?” In 1840, the Hartford Courant shared a piece from Silliman’s Journal entitled “On the Tails of Comets,” which addressed the still-unresolved question of the composition of comet’s tails and explored competing theories.

Many readers noted Sam’s critique of missionaries in this piece, and the broader connection between space fantasies and imperialism. While Sam was critical of missionaries–and of the apparent violence necessary to ensure those who had paid for the cruise had a pleasant time–other writing about space at the time embraced the connections between religion, science, discovery, and conquest. Morgan’s “Glimpses of Other Worlds” is full of uncritical language reminiscent of 19th century colonizers from Europe and the United States–language of science, of discovery, of entitlement, and of enrichment.

Why before I was out of my teens I had explored every nook of our little globe and then as Alexander wept because there were no more worlds to conquer I wept because there were no more to visit.

In truth we were not blind to the probable dangers of the attempt. Nevertheless in the glorious cause of science a small band of enthusiasts were found willing to undertake the arduous duty and steel their souls to the perils of the way Government had guaranteed in the event of our not returning within a prescribed period to send out a party . . . to search for our bodies and provide us with a decent burial.

My first care was to take a survey . . . I was immeasurably astonished at the inconceivable richness and fertility of the soil. Half an acre of land abundantly sufficed to support half a dozen families in affluence . . . Every where might be seen towering trees producing fruits, daintier far than the pine or the pomegranate, every where there sprung up spontaneously the rarest exotics of most varied hue richest perfume.

Where does this piece fit in Twain’s personal and professional life?

P.T. Barnum and Mark Twain met in the 1870s and their acquaintanceship quickly became a great friendship. According to Barnum’s recollections, Twain was often a guest at Barnum’s home Waldemere in Bridgeport Connecticut. A letter dated May 24, 1875 from Twain to Barnum captures the great affection they had for each other.

I was delighted yesterday morning at breakfast to learn that Mr. Barnum was in the library. When I got there, it was Mr. Barnard – a stranger who had cause to put in his time and put out mine. I ought to have killed him, but as it was Sunday, I let him go. Many thanks for the last installment of letters. I am learning to play the pig-tail whistle.

The last two sentences allude to a favorite pastime between the two of exchanging letters. As some of the most famous eccentrics of their day, Twain and Barnum understandably received many letters from strangers who ran the gamut from beggars to those down on their luck to general eccentrics. Barnum received a lot more than Twain and as such would send them in batches, much to Twain’s amusement.

According to an interview with Barnum in the New York World, Livy Clemens and Barnum’s wife (Nancy Fish) were also good friends. Barnum claims that when Twain was telling a story, Nancy would always look at Livy’s face. If Livy was quiet, it was an old story that she had probably heard a hundred times, if she laughed, that meant it was probably a fresher story.

Excerpt from “A Curious Pleasure Excursion” New York Herald, July 6, 1874

This is to inform the public that in connection with Mr. Barnum I have leased the comet for a term of years . . . We propose to fit up comfortable, and even luxurious, accommodations in the comet . . . and make an extended excursion among the heavenly bodies. We shall prepare 1,000,000 state rooms in the tail of the comet (with hot and cold water, gas, looking glass, parachute, umbrella, &c. in each) . . . We shall have billiard rooms, card rooms, music rooms, bowling alleys and many spacious theatres and free libraries.

Hostility is not apprehended from any great planet, but we have thought it best to err on the safe side, and therefore have provided a proper number of mortars, siege guns and boarding pikes . . . We shall hope to leave a good impression of America behind us in every nation we visit, from Venus to Uranus. And, at all events, if we cannot inspire love we shall, at least, compel respect for our country wherever we go. We shall take with us, free of charge A GREAT FORCE OF MISSIONARIES and shed the true light upon all the celestial orbs which physically aglow, are yet morally in darkness. Compulsory education will be introduced . . .

FIRST CLASS FARE from the Earth to Uranus, including visits to the Sun and Moon and all principal planets on the route, will be charged at the low rate of $2 for every 50,000,000 miles of actual travel . . . This comet is new and in thorough repair and is now on her first voyage. She is confessedly the fastest on the line. She makes 20,000,000 miles a day, with her present facilities; but, with a picked American crew and good weather, we are confident we can get 40,000,000 out of her.

The entire voyage will be completed, and the passengers landed in New York again on the 14th of December, 1991. This is at least forty years quicker than any other comet can do it in . . .