Welcome to Sam’s Shorts! Each month we bring you a brief passage from one of Mark Twain’s less-familiar works, inviting you to read, reflect, and respond. Then we share what we learned from your responses, answer some of your questions, and tell you a bit more about the background and context of the piece. You can read the current Sam’s Shorts selection here.

In the winter of 2021, we shared a selection from Twain’s travel work Following The Equator from 1897 in which he described the splendor of an ice storm.

Reader reflections

Nearly all of our readers loved one particular section: when Clemens described the sun shining through ice-covered trees, turning them into “a glory of white fire” and “a spouting and spraying explosion of flashing gems of every conceivable color . . .”

Several readers liked that he recognized the way the aftermath of an ice storm elicited wonder among everyone in the house, “the little and the big.”

It’s not surprising that so many readers liked that particular line, because this whole passage made people remember their own ice storm experiences:

Having experienced a few Hartford ice storms in my day, I felt I was standing right alongside Sam while he and his family were awed by one of Nature’s special spectacular displays.

This passage reminded me of growing up near Hartford and experiencing an infamous ice storm in the 1970s. Although we were without power for weeks due to the widespread damage, and driving or even walking outside could be dangerous, the landscape looked like a crystalline winter wonderland! So beautiful!

The times that I thought about how beautiful everything looked covered in ice with the sun glinting off it while I stood outside my house that had no electricity or heat because of the ice storm!! Worth the trade off – I’d get the power back but not the sight or feeling.

I’ve never experienced an ice storm in Connecticut, but have lived though several in Kansas, Oklahoma and Missouri where with the ice and wind they can certainly wreak havoc and a maze of broken limbs and trees and often downed electrical lines.

Despite Clemens’ emphasis on the beauty of the ice storm, most readers couldn’t help but think of the destruction that comes along with that ice.

It is very descriptive . . . The passage takes us from the beginning to the middle to the end of the storm. Winter often times represents death in literature. Yet at the end, the sun is high in the sky and the ice looks like gems.

The dual nature of an ice storm. The beauty of it, and the damage and dangers it brings.

Where does this piece fit in Twain’s personal and professional life?

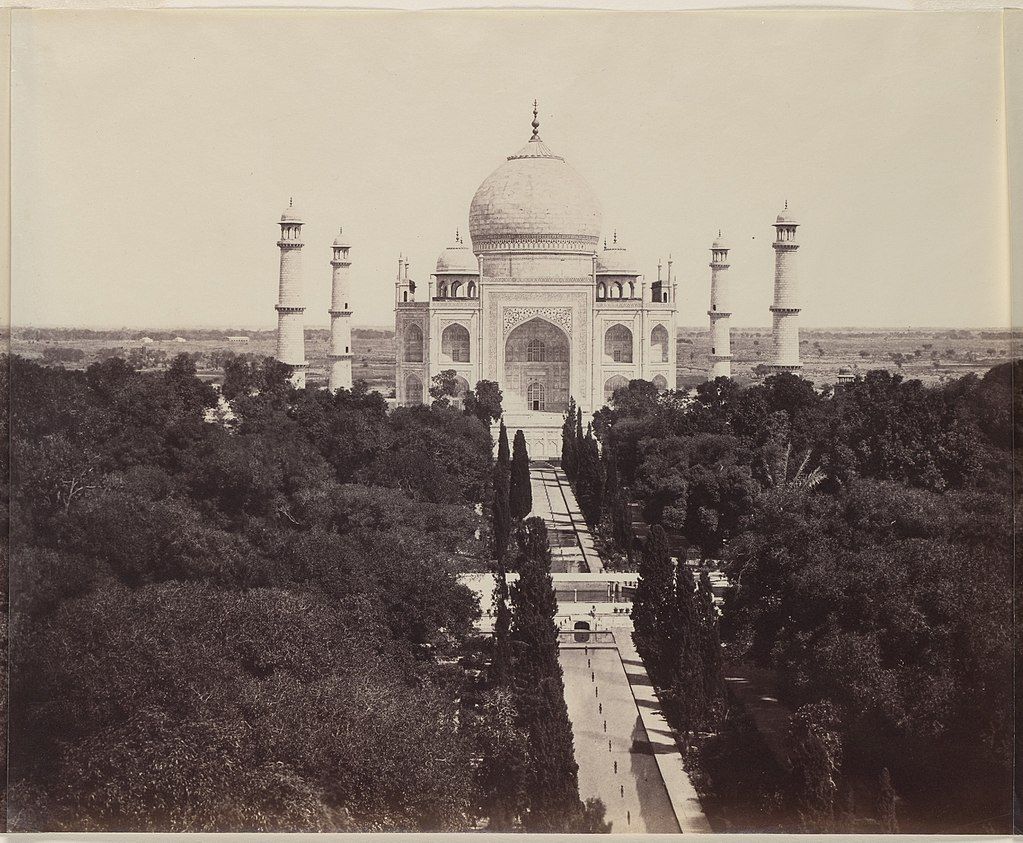

This selection is drawn from Following the Equator, published in 1897, six years after Sam’s bad business dealings led to financial losses so severe the Clemenses were forced to leave their Hartford home. The world-wide lecture tour that helped him recoup those losses led to the writing of Following the Equator itself. In that book, this passage about the ice storm was used to frame Clemens’ visit to the Taj Mahal. Here’s the paragraph that preceded the selection we shared:

I suppose that many, many years ago I gathered the idea that the Taj’s place in the achievements of man was exactly the place of the ice-storm in the achievements of Nature; that the Taj represented man’s supremest possibility in the creation of grace and beauty and exquisiteness and splendor, just as the ice-storm represents Nature’s supremest possibility in the combination of those same qualities . . . the Taj has had no rival among the temples and palaces of men, none that even remotely approached it—it was man’s architectural ice-storm.

But this passage about the ice storm wasn’t originally written for Following the Equator. It first appeared in a speech you may be familiar with, one Clemens gave in 1876 at the New England Society annual dinner at Delmonicos in New York City. The subject: New England weather.

Yes, one of the brightest gems in the New England weather is the dazzling uncertainty of it. There is only one thing certain about it, you are certain there is going to be plenty of weather . . . You fix up for the drought; you leave your umbrella in the house and sally out with your sprinkling pot, and ten to one you get drowned.

At the end of his speech, Clemens offered the passage on the beauties of the ice storm as a counterweight to his criticism of New England’s weather. He closed the speech by asserting:

Month after month I lay up my hate and grudge against the New England weather; but when the ice storm comes at last, I say: “There, I forgive you, now; the books are square between us; you don’t owe me a cent; go, and sin no more; your little faults and foibles count for nothing; you are the most enchanting weather in the world!”

Speechmaking was a big part of how Clemens built his brand—and his fortune!—so it’s not surprising that it’s part of what helped him rebuild those things in the 1890s. And who could blame him for revisiting and expanding on the endlessly-beautiful ice storm?

“…the mischief they play with the electric wires.”

Many readers felt that Clemens’ focus on the beauty of ice storms may have felt more possible because ice storms would have had less of an impact on people’s lives compared to today.

In Mr. Clemens’ time homes were more self-sufficient than today’s connected home with electricity now a necessity, and so vulnerable to an ice storm’s ravages.

Most readers, in fact, asserted that an ice storm would have been less inconveniencing to people in the Gilded Age, who would have, in turn, been less put out by the potential for severe weather.

I wonder what Twain would make of today’s media hype regarding severe weather events.

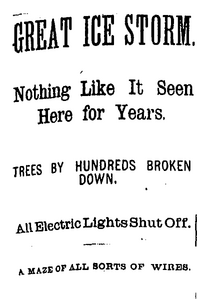

But a glance through newspapers in 19th century Connecticut makes clear that severe weather, including ice storms, was dangerous and destructive—to people’s lives and property, to the economy, and to the general functioning of society.

But a glance through newspapers in 19th century Connecticut makes clear that severe weather, including ice storms, was dangerous and destructive—to people’s lives and property, to the economy, and to the general functioning of society.

Unsurprisingly, tree damage was the major concern in nearly all newspaper articles about ice storms, which could ruin an orchard–and a family’s income–overnight. For instance, an ice storm in late March 1837 devastated Litchfield, a town to the west of Hartford (and birthplace of Harriet Beecher Stowe): “The peach trees are almost entirely destroyed, the pear, the plum, the apple, and indeed all kinds of fruit and forest trees, are more or less damaged . . .”

Many readers presumed the lack of widespread home electrification might make ice storms less disruptive in the Gilded Age. Certainly the Clemenses wouldn’t have had to worry about whether their power (or internet!) went out, but there were still plenty of wires to be pulled down and the effects could be far more disruptive than downed trees and branches across the roads.

Gilded Age Hartford began transitioning from municipal gaslighting to electric lighting in the early 1880s, and ice storms regularly pulled down wires and poles. After a storm, the hushed creaking of icy tree branches would quickly give way to the sound of fire alarms going off—at first, false alarms all over the city from ice weighing down the wires, and then more regular alarms as the fire department repaired and tested the system in the following days. The ice also brought down telephone wires, something that would absolutely have affected the Clemens home, though perhaps not as severely as it did one Hartford resident whose bedside telephone caught on fire as a result of crossed wires!

“Ice storm, Winter of 1890. Colony Street North from Columbia.” A stereoscopic view of New Haven’s ice-laden wires.

In fact, the local papers were often filled with local news like this–a man using kerosene to try to melt the ice, records of notable trees that had been felled, a half-column spent describing a particularly embarrassing fall witnessed by a reporter–because there was no way to get news from outside of the city in the immediate aftermath of an ice storm.

Of all the wires that such a storm might bring down, it was the telegraph wires that had the greatest impact on the lives of Hartford residents. The advent of widespread electrical telegraph systems in the United States in the mid-19th century had transformed how information traveled, and they were still the dominant mode of rapid communication, despite the introduction of telephones. When the telegraph wires were down, the residents of a city like Hartford couldn’t get news, but they also couldn’t get goods. Telegraph systems were vital to the coordination of the railways, and between downed wires and downed trees, train service could be stalled for days as the result of an ice storm.

An important point to close with: Sam Clemens was singular in many ways, but not in his desire to celebrate the beauty of ice storms. Alongside all of these newspaper accounts of downed trees and wires you were almost guaranteed to find some bit of poetry or prose from a newspaper reporter or member of the public inspired by the beauty they saw alongside the destruction, even if it was just wishful thinking: “If the sun had come out there would have been a scene of wonderful beauty.” Thankfully, Hartford residents look forward to the next sunny day that might illuminate (and then melt!) the ice, and they could even have a good idea when that day would next come, thanks to more accurate weather forecasting that had only recently become possible because of widespread electric telegraph systems.

From Following The Equator, 1897

Here in London the other night I was talking with some Scotch and English friends, and I mentioned the ice-storm, using it as a figure—a figure which failed, for none of them had heard of the ice-storm. One gentleman, who was very familiar with American literature, said he had never seen it mentioned in any book . . .

The oversight is strange, for in America the ice-storm is an event. And it is not an event which one is careless about. When it comes, the news flies from room to room in the house, there are bangings on the doors, and shoutings, “The ice-storm! the ice-storm!” and even the laziest sleepers throw off the covers and join the rush for the windows. The ice-storm occurs in midwinter, and usually its enchantments are wrought in the silence and the darkness of the night. A fine drizzling rain falls hour after hour upon the naked twigs and branches of the trees, and as it falls it freezes. In time the trunk and every branch and twig are incased in hard pure ice; so that the tree looks like a skeleton tree made all of glass—glass that is crystal-clear.

. . . The dawn breaks and spreads, the news of the storm goes about the house, and the little and the big, in wraps and blankets, flock to the window and press together there, and gaze intently out upon the great white ghost in the grounds, and nobody says a word, nobody stirs. All are waiting; they know what is coming, and they are waiting—waiting for the miracle . . . at last the sun fires a sudden sheaf of rays into the ghostly tree and turns it into a white splendor of glittering diamonds. Everybody catches his breath, and feels a swelling in his throat and a moisture in his eyes-but waits again; for he knows what is coming; there is more yet. The sun climbs higher, and still higher, flooding the tree from its loftiest spread of branches to its lowest, turning it to a glory of white fire; then in a moment, without warning, comes the great miracle, the supreme miracle, the miracle without its fellow in the earth; a gust of wind sets every branch and twig to swaying, and in an instant turns the whole white tree into a spouting and spraying explosion of flashing gems of every conceivable color . . .

By all my senses, all my faculties, I know that the icestorm is Nature’s supremest achievement in the domain of the superb and the beautiful . . .