Who Was George Griffin?

Years after leaving Hartford, Sam Clemens recalled George Griffin, the Black man employed as butler to the Clemens family during their time there.

George was an accident. He came to wash some windows, and remained for half a generation. He was a Maryland slave by birth; the Proclamation set him free, and as a young fellow he saw his fair share of the Civil War as body servant to General Devens. He was handsome, well built, shrewd, wise, polite, always good-natured, cheerful to gaiety, honest, religious, a cautious truth-speaker, devoted friend to the family, champion of its interests, a sort of idol to the children and a trial to Mrs. Clemens–not in all ways but in several . . . There was nothing commonplace about George. He had a remarkably good head; his promise was good, his note was good; he could be trusted to any extent with money or other valuables . . . he had the respect and I may say the warm friendly regard of every visiting intimate of our house.

These recollections, published in A Family Sketch, provide one of the most complete accounts of George Griffin’s life and personality that we know of. But Sam’s description asks as many questions as it answers.

- What was George’s life like when he was enslaved?

- How did he end up in Hartford?

- Would the Clemens family really hire someone who just showed up to wash the windows?

- What did he actually do as a butler?

- What was his life like outside of his work for the Clemens family?

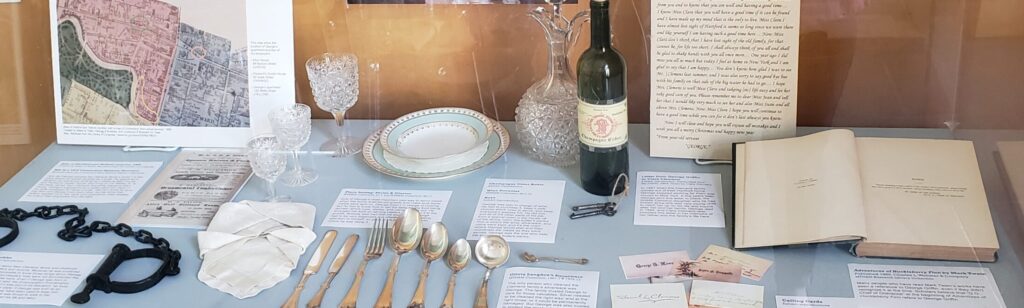

“Who Was George Griffin?” uses objects and images to answer some of these questions, and to explain why some of them are difficult, or nearly impossible, to answer. It was curated by My’kelle Coleman, a junior at Hartford Public High School, with the help of Erin Bartram, School Programs Coordinator, and Jodi DeBruyne, Beatrice Fox Auerbach Director of Collections. My’kelle’s work was supported by the ReadyCT Summer Internship Program. The exhibit is located in the Nook Cafe at The Mark Twain House & Museum and will be up through the end of the year.

Beyond the challenges of answering questions about the lives of enslaved people that are examined in the exhibit itself, questions still remain about George’s life in Hartford outside of his work for the Clemens family. Sam provides us with some more tantalizing details about that life.

. . . [George] was strenuously religious, he was a deacon and autocrat of the African Methodist Church . . . he acquired a house and a wife not very long after he came with us . . . He ruled his race in the town, he was its trusted political leader . . . His people sought his advice in their troubles, and he kept many a case of theirs out of court by settling it himself . . . He was an earnest Republican . . .

In Sam’s recollection, George was a part of several important communities in Hartford outside his work for the Clemens family. He also had a family of his own.

In Sam’s recollection, George was a part of several important communities in Hartford outside his work for the Clemens family. He also had a family of his own.

Over the years, many at the museum have tried to find out more about these parts of George Griffin’s life, using our own collections, materials held in other museums and archives, and interviews with Hartford residents. But we know there may be more historical documents, images, and community knowledge held by people and organizations in Hartford that could shed light on aspects of his life.

If you think you might know something that could help us learn more about George’s life, or if you simply want to share your thoughts on this exhibit, please use the form below. Be sure to leave your email if you have documents or community knowledge you want to share!