Dianthus

Dianthus are also known as “pinks.” In Practical Floriculture, Henderson states: “The Pinks are numerous and varied, many of them having a rich, clove fragrance. They present an endless variety in color and style of flower.” Pinks include flowers like the ones we have growing in our garden as well as other forms you might be more familiar with from the florists, like carnations.

The Clemens family’s second gardener, John O’Neill, was well known in Hartford for his beautiful dianthus. The Hartford Times mentioned his skill in a May 1890 report on a local flower show:

Mr. John O’Neil, for the past five years gardener for Mr. Samuel L. Clemens, exhibits six varieties of pinks, among them the well known Hartford Seedling and the Portia.

The Portia was a scarlet carnation variety that had just been introduced to American gardens in the 1880s, but though it might have been “well known” in the Gilded Age, we’re not sure what the Hartford Seedling variety looked like!

Photo credit: Sabina Bajracharya, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Daffodils

In spring, you’ll see a lot of daffodils in the Twain gardens. They bloom March through May in a variety of yellows, whites, oranges, and pinks, and their hardiness made them “of utmost consequence to the flower gardener,” in Henderson’s opinion. We certainly make good use of them here! Daffodils are in the genus narcissus, named for the character from Greek mythology who was so captured by his own beautiful reflection in the water that he stared at himself until he was turned into a flower.

The town is budding out, now—the grass & foliage are, at least—& again Hartford is becoming the pleasantest city, to the eye, that America can show. –Sam Clemens to Livy Clemens, 12 May 1869

Photo credit: Wilhelm Zimmerling PAR, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Grape Hyacinths

Grape hyacinths (Muscari armeniacum) share a name and bloom at the same time in the spring as the larger hyacinths you may be familiar with, but they are two different species of flower altogether. Grape hyacinths can be planted and remain in the ground for many years. “On the east end of Long Island,” Henderson claimed, “some fields are literally blue with the flowers in early spring.”

Photo credit: daryl_mitchell from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada,CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Woodland stonecrop

Woodland stonecrop is a plant native to many forest spaces in Eastern North America. Like all plants in the genus Sedum, stonecrop is a succulent—a plant with leaves that are fleshy and full of moisture to help them survive in dry soil. Succulents are popular houseplants today. Do you know of any? Henderson thought stonecrop was a valuable ornamental plant in particular spots in the garden: “Locations where rocks exist in their natural condition can often be made highly interesting and ornamental by setting out plants of a drooping or trailing habit to overhang among them.” What do you think he meant by rocks “in their natural condition”?

Photo credit: Guettarda, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hostas

You’ll find hostas in a number of gardens at the museum–and maybe in your own garden. These plants, originally native to Japan, are easy to spot because of their distinct foliage. Peter Henderson actually lists them under the name “Day Lily,” but they’re not the same as what we in the U.S. call daylilies today—look for those in some of the other gardens! He says they make good border plants because their leaves are so nice and because they don’t spread much from where you’ve planted them. Hostas are perennials that do well in places that get some shade. Did you find them in shade or in sunlight?

Photo credit: Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Lavender

Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) is often known as “English lavender,” but it and the other flowers in the genus originate in the Mediterranean and South Asia. Even though it’s from warmer climates than New England, it’s a hardy evergreen perennial shrub in our gardens. If it’s blooming, you can probably smell the fragrant flowers. Peter Henderson noted that all kinds of lavender were highly valued: “The essential oil of Lavender is produced by distillation from the flowers and is much prized for its agreeable odor.” This essential oil was used to make perfume and to give a pleasing scent to laundered clothes, much as it is today. Our gardens have two varieties of lavender: L. angustifolia “Hidcote” and L. angustifolia ‘Phenomenal.”

Photo credit: Acabashi, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Creeping Thyme

The creeping thyme in our gardens is part of the same genus but is not the same plant as the thyme you might be familiar with in the kitchen. Peter Henderson said of this kind: “There are probably a hundred acres of Thyme grown in the vicinity of New York and dried for flavoring purposes.” He did think flowering thyme was an excellent plant for gardens, however. You’ll notice it is a low mounding perennial plant with beautiful flowers; he thought it was exceptionally useful for borders.

Our creeping thyme used to be in a different garden at the house, but it wasn’t doing well there, so our gardeners moved it over to the Rose Garden. It seems to love its new location!

Photo credit: Jason Hollinger, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Holly

Holly is an evergreen, deciduous shrub in the genus Ilex. It may be familiar to you as a Christmas plant with its bright red berries and dark green spiky leaves. Holly plants are generally dioecious, meaning they have male plants and female plants. We have two Ilex × meserveae holly plants here, commonly known as Blue Prince and a Blue Princess; the Blue Prince is the one that blooms with small white flowers, and the Blue Princess is fertilized by those flowers and develops the familiar red berries. While the plants normally grow separately, it is is also possible to have a holly bush that is both male and female.

Photo credit: Neelix at English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roses

Anna brought flowers from Sue; & Livy made some handsome bouquets, & immediately grew riotous & disorderly because, she said, “Nobody ever comes to call when we have fresh flowers.” Well, somebody had better come—else I will take a club & go & invite half a dozen or so. Our flowers are not to go to waste this time, merely for want of a little energetic affability. –Sam Clemens to Jervis and Olivia Lewis Langdon, 27 March 1870

Rose gardening has such a long and complex history that Peter Henderson dedicated six pages to it in his 1881 Handbook of Plants and General Horticulture.

The Clemens family’s gardener, John O’Neill, was well known for the roses he cultivated here. In 1890, he exhibited some of them at the Horticultural Society’s show in March. The Hartford Times reported:

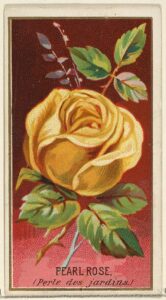

Among the roses are some beautiful specimens of the Cornelia Cook and the Bride, beautiful white roses; a magnificent Pearl des Jardins, rich yellow, the La France, the Catherine de Mermet and many others. Perhaps the most admired among his collection is a fine specimen of the Sunset rose. This is luxuriant in size and form, and in color a delicate yellow with rich saffron heart.

Livy Clemens often called upon John to send cut flowers from the greenhouse–especially roses–to friends celebrating important events, and made note of what varieties of roses people had in their wedding bouquets.

Rose gardening has come a long way in the century and a half since the Clemenses had roses here. Most of the roses John O’Neill grew were considered “tea roses,” which had been introduced to Europe and the U.S. from Asia in the 19th century. Roses come in lots of different shapes, but 19th century tea roses helped create the classic rose shape you’re probably thinking of right now.

Photo credit: Goodwin & Company, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tea roses were repeat-flowering, meaning they could bloom more than once in a season, but they didn’t do so well in cooler climates. 19th century rose gardeners crossed them with the roses that were common in England–which were hardier but didn’t bloom as much–to come up with the hybrid tea rose.

The La France that John O’Neill grew here was the very first variety of hybrid tea, introduced less than a decade before the Clemens family moved into this house. The Beverly Eleganza we grow here today is a modern hybrid tea.

Photo credit: Salicyna, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Two of our roses, Pretty Polly White and The Fairy, are polyantha roses. You’ll notice they have much smaller blooms than the Beverly Eleganza–but the bushes are covered with blooms! That’s where their name comes from; in Greek, “poly” means many and “anthos” means flower. Polyantha roses are usually shades of white, red, and pink.

Photo credit: Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Julia Child is a floribunda, a group of roses that came from crossing polyantha and hybrid tea roses in the early 20th century. Floribunda roses have the range of colors of hybrid teas but bloom as much as polyantha roses.

Photo credit: In twilight, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Most of the roses in our garden were donated by the Heritage Rose Foundation, but the Julia Child came from one of our dedicated volunteer gardeners. You may notice there are more roses in our garden than on our scavenger hunt. That’s because we have two mystery roses! They were gifts to our gardens, and we aren’t sure exactly what varieties they are.

Help us map the different microclimates here at the museum! Use your observational skills to check off every plant you see blooming in the Rose Garden on the day you visit. When you’re done, hit “Submit,” and then follow the link provided to learn about everything growing in this garden—including what you helped us track!

At the end of the season, we’ll hold a drawing and three of the people/families who participated in the scavenger hunt this summer will receive a special gift from the museum. Enter your email address at the end of the form if you’d like to be in the running.

The Rose Garden is on the museum patio; turn to your right when you leave the museum center from the upper floor, and you’ll find it at ground level around the outside of the walled-off Sundial Garden.

Livy's Rose Garden Scavenger Hunt