Welcome to Sam’s Shorts! Each month we bring you a brief passage from one of Mark Twain’s less-familiar works, inviting you to read, reflect, and respond. Then we share what we learned from your responses, answer some of your questions, and tell you a bit more about the background and context of the piece. Remember to read the current Sam’s Shorts selection and check out other selections we’ve explored.

Our second Sam’s Shorts selection came from “A Presidential Candidate.” Twain sent it to the New York Evening Post in late May 1879 and it was published on June 9 under the headline “Mark Twain, a Presidential Candidate,” framed as a letter to the editor.

Reader reflections

While this selection was shared far and wide on social media, with hundreds of Facebook reactions, readers were far more hesitant to share their responses with us directly. Those who did wanted to know about the specifics of the political moment that led Twain to write such a piece, but also noted similarities to our present political situation. One reader mused:

I wonder if people are surprised that politics were much the same then as they are now.

If you saw something familiar in Twain’s thoughts about the presidency, were you surprised?

Where does this piece fit in Twain’s personal and professional life?

Clemens wrote “A Presidential Candidate” in Paris as he and his family were nearing the end of an eighteen-month trip through Europe.

It is tempting to read this 1879 piece as a commentary on the 1880 presidential election, in which Twain provided rousing public support to the successful Republican candidate James Garfield. But just as someone writing in May 2019 had no idea what the presidential match-up of 2020 would ultimately look like, electoral politics in the Gilded Age were similarly fluid.

Neither the current president, Republican Rutherford B Hayes, nor his Democratic opponent in the previous election, former New York governor Samel Tilden, were planning to run in 1880. So when Twain wrote this piece in 1879, he couldn’t know for sure who the nominees would be the following year. In fact, in a letter to William Dean Howells near the beginning of his European trip, he expressed deep satisfaction at having “unplugged,” so to speak:

Ah, I have such a deep, grateful, unutterable sense of being “out of it all” . . . I don’t read any newspapers or care for them. When people tell me England has declared war, I drop the subject, feeling that it is none of my business . . .

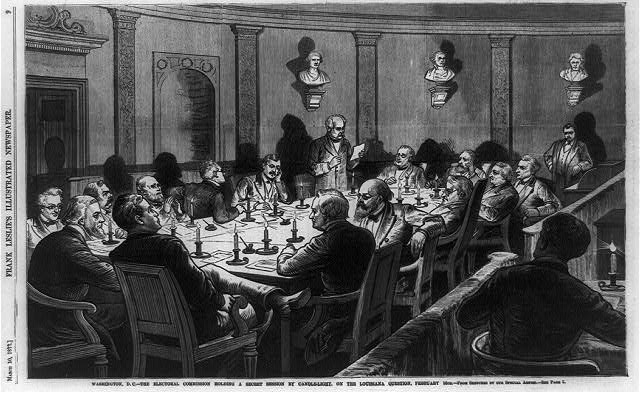

But the piece makes it clear that Twain was still thinking about one of the central issues of American electoral politics in this period: corruption. The 1876 election had been decided by an electoral committee commissioned by Congress to award a handful of disputed electoral votes from four states; the committee voted along party lines to award the electoral votes to Hayes, making Tilden the only candidate ever to win an outright majority of the popular vote and lose the election. Yet an 1878 investigation had also discovered irregularities, including bribery, in the Tilden campaign.

Eliminating political corruption had been important to Twain in his choice to support Hayes in the 1876 election, and while he would remain a staunch Hayes supporter, his commitment to clean government and good character in elected officials would eventually lead him to a painful break with the Republican party. In the 1884 presidential election, Twain aligned himself with the “Mugwumps”: Republicans who chose to support the Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland because their own party had nominated someone they saw as politically corrupt.

What about that Valley Forge thing?

Clemens’ reference to George Washington praying at Valley Forge may be familiar to you. Like the story of the cherry tree, it first appeared in the early 1800s from the pen of Mason L. Weems. “Parson” Weems told the story of Isaac Potts, who was passing by the American army’s headquarters at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777 when he heard a voice “speaking much in earnest.” It was Washington himself, “in a dark natural bower of ancient oaks . . . on his knees at prayer.” When Potts arrived home, he rushed to tell his wife what he had seen—and what it meant to him.

I have this day seen what I never expected. Thee knows that I always thought that the sword and the gospel were utterly inconsistent; and that no man could be a soldier and a christian at the same time. But George Washington has this day convinced me of my mistake . . . If George Washington be not a man of God, I am greatly deceived—and still more shall I be deceived, if God do not, through him, work out a great salvation for America.

Twain admired Washington as well, but in a different way. In 1886, having experienced strain in several close relationships over his decision to vote against his party in the last presidential election, he argued that the ability to think independently, the Mugwump way, was not only vital for personal voting choices, but for political leadership itself:

. . . in the whole history of the race of men no single great and high and beneficent thing was ever done for the souls and bodies, the hearts and the brains of the children of this world, but a Mugwump started it and Mugwumps carried it to victory. And their names are the stateliest in history: Washington, Garrison, Galileo, Luther, Christ.

From “A Presidential Candidate,” published June 9, 1879

I have pretty much made up my mind to run for President. What the country wants is a candidate who cannot be injured by investigation of his past history, so that the enemies of the party will be unable to rake up anything against him that nobody ever heard of before. If you know the worst about a candidate, to begin with, every attempt to spring things on him will be checkmated. Now I am going to enter the field with an open record. I am going to own up in advance to all the wickedness I have done, and if any Congressional committee is disposed to prowl around my biography in the hope of discovering any dark and deadly deed that I have secreted, why—let it prowl.

. . . I candidly acknowledge that I ran away at the battle of Gettysburg. My friends have tried to smooth over this fact by asserting that I did so for the purpose of imitating Washington, who went into the woods at Valley Forge for the purpose of saying his prayers. It was a miserable subterfuge. I struck out in a straight line for the Tropic of Cancer because I was scared. I wanted my country saved, but I preferred to have somebody else save it. I entertain that preference yet . . .

. . . The rumor that I buried a dead aunt under my grapevine was correct. The vine needed fertilizing, my aunt had to be buried, and I dedicated her to this high purpose. Does that unfit me for the Presidency? The Constitution of our country does not say so. No other citizen was ever considered unworthy of this office because he enriched his grapevines with his dead relatives. Why should I be selected as the first victim of an absurd prejudice?

. . . These are about the worst parts of my record. On them I come before the country. If my country don’t want me, I will go back again. But I recommend myself as a safe man—a man who starts from the basis of total depravity and proposes to be fiendish to the last.