Welcome to Sam’s Shorts! Each month we bring you a brief passage from one of Mark Twain’s less-familiar works, inviting you to read, reflect, and respond. Then we share what we learned from your responses, answer some of your questions, and tell you a bit more about the background and context of the piece. You can read the current Sam’s Shorts selection here.

Our third Sam’s Shorts selection came from “As Regards Patriotism.” This piece was written in 1901 and was first published in Europe and Elsewhere, a collection of Twain’s writing edited and released by Albert Bigelow Paine in 1923.

Reader reflections

Readers noted Twain’s focus on the media as the arbiter of patriotism in this short excerpt, particularly its powers of “persuasion and control through fear and shame.” Two lines stood out as particularly notable to readers:

“The newspaper-and-politician-manufactured Patriot often gags in private over his dose; but he takes it, and keeps it on his stomach the best he can. Blessed are the meek.”

“the windy and incoherent six-dollar sub-editor of his village newspaper”

Those who responded to the piece wanted to know what was going on in 1901 that prompted Twain to write this and whose behavior, in particular, may have inspired this condemnation.

Where does “As Regards Patriotism” fit into Twain’s personal and professional life?

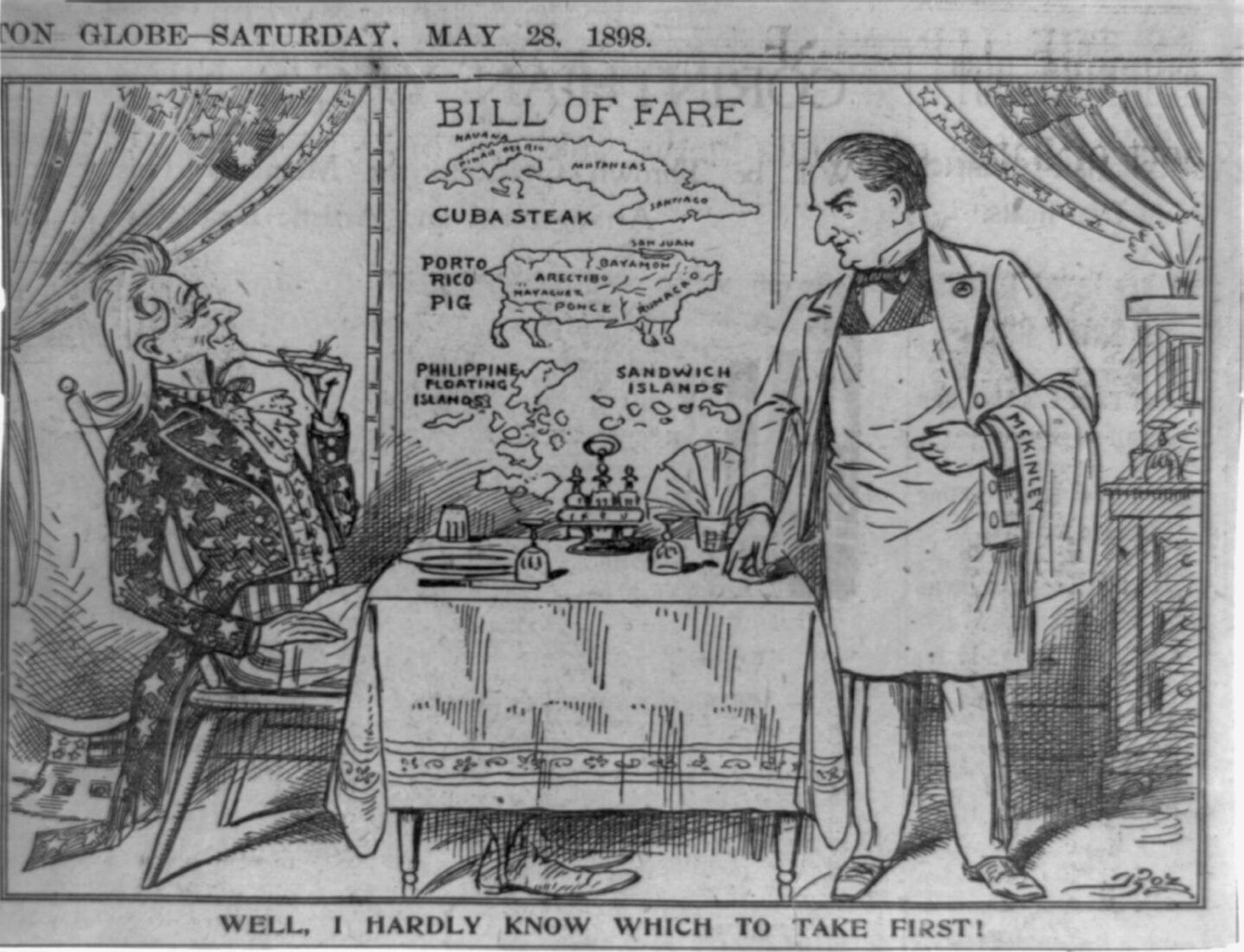

Twain and his family were living in New York in 1901, and the piece was part of a flurry of his writing and speaking in opposition to U.S. overseas imperialism in the wake of the 1898 Spanish-American War, during which the United States had sought to “liberate” valuable Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific. During the war itself, while living in Europe, Twain had actually composed a piece in support of the war, encouraging Americans to resist European attempts to shame them for their country’s actions:

“Brutal, base, dishonest? We? Land thieves? Shedders of innocent blood? We? Traitors to our official word? We? Are we going to lose Europe’s respect because of this new and dreadful conduct?”

He had been critical of some U.S. overseas colonialism in the past, as in some of his speeches on the annexation of Hawai‘i, but upon his return to the states in October 1900, he became a vocal opponent of ongoing U.S. military efforts after the end of the war with Spain to “liberate” the population of the Philippines into accepting a relationship favorable to U.S. interests. Twain expressed this new opinion in speeches, interviews, and even an officer’s position in the Anti-Imperialist League. His change of heart, as he explained in an interview in the New York Herald in October 1900, had come from reading and reconsideration:

“But I have thought some more, since then, and I have read carefully the treaty of Paris [which had officially ended the war with Spain] , and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. . .”

Yet both his defense of U.S. intervention in these Spanish colonies and his eventual denunciation of a continued war in the Philippines imply a similar belief: that there could be a right way to do colonialism. Moreover, given that the U.S. had attempted to purchase Cuba during Twain’s lifetime, and that powerful Americans invested in the expansion of slavery had funded and participated in private military interventions on the island with the goal of annexing it during that same period, it is perhaps fair to wonder about the extent to which Twain and his contemporaries gave this venture the benefit of the doubt.

Censorship, colonialism, and corn-pone

But, of course, that is one of the central issues considered in this piece. “As Regards Patriotism” focuses on the self-censorship that comes from fear of criticism in your own small town or among your own community. In this case, the ideological “conformity” that irked Twain manifested in two related points: that the war in the Philippines was a good war and that being a patriot meant supporting your country whatever decisions its government and people made.

Many who read and responded to this short raised the issue of freedom of speech, but it’s worth noting that this piece isn’t about government interference or censorship. It’s not even about newspapers refusing to publish certain people or perspectives, though this was the heyday of so-called “yellow journalism,” in which newspaper magnates whipped up public support for war with Spain through sensational stories. Instead, it’s about the way our immediate social, economic, and personal relationships can lead us to go along with things we don’t agree with, or keep silent when we fear our views will earn us censure. In a January 1901 letter, he rebuked his close friend Joseph Twichell, minister at Hartford’s Asylum Hill Congregational Church, for advising him to temper his public anti-imperialist sentiment:

“. . . if you teach your people—as you teach me—to hide their opinions when they believe the flag is being abused and dishonored, lest the utterance do them and a publisher damage, how do you answer for it to your conscience?”

It was important to Twain that he had reconsidered his views on the war, arrived at a new—and unpopular—opinion, and then publicly affirmed that new opinion, even in the face of criticism from close friends. As a result, his writing in this period was as concerned with these issues as it was with anti-imperialism itself. During this same year, he wrote “Corn-Pone Opinions,” perhaps his most well-read consideration of fashion, conformity, and public opinion:

“We all do no end of feeling, and we mistake it for thinking. And out of it we get an aggregation which we consider a boon. Its name is Public Opinion. It is held in reverence. It settles everything. Some think it the Voice of God.”

But though Twain criticized these kinds of social pressures and the conformity that resulted from them, he wasn’t immune to their effects. In the summer of 1901, Twain decided he wanted to write a book about lynching, asked Frank Bliss, the president of Twain’s long-time publishers, to send him all of the information he could on the subject, and drafted a short piece: “The United States of Lyncherdom.” But a few days later, he pressed pause on the enterprise in another letter to Bliss, worried about what such a book might do to the business of another publisher with whom Bliss’ American Publishing Company had just begun marketing a new complete edition of Twain’s works:

“No, upon reflection it won’t do for me to write that book if Mr. Newbegin values his Southern Trade, for I shouldn’t have even half a friend left, down there, after it issued from the press. You have probably already thought of that. It is a pity. I think I could make a book that would make a splendid stir—in fact I know it. I shan’t destroy the article I have written, but I see it won’t do to print it. I shall keep it, & wait. There is considerable vitriol in it, & that will keep it from spoiling.”

This piece, like “Corn-Pone Opinions” and “As Regards Patriotism,” went unpublished until after Twain’s death. In the reference work Mark Twain Day By Day, David Fears notes: “Sam felt someone should write such a book but could not think of the right man.”

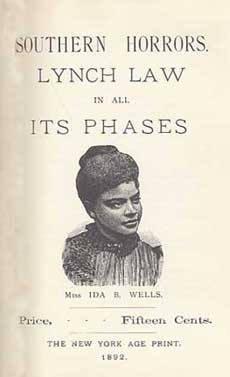

In fact, someone had already written it. In 1892, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a Black woman who had been born into slavery in Mississippi during the Civil War, had published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All its Phases. Wells-Barnett, a teacher and journalist who had been writing about racism and engaging in activism in Memphis for nearly a decade by that point, had turned her writing focus to this issue following violence and the eventual lynchings of several successful Black grocery store owners and workers in that city in March 1892. She was particularly critical of the way the white press enabled this violence.

Southern Horrors was drawn from material she published in the New York Age in June 1892. She had been on vacation in New York the previous month when a white mob, furious with a recent editorial on lynching, attacked and destroyed the printing offices of the newspaper where she served as editor: the Memphis Free Speech.

Given all this, it is worth considering whether we think about patriotism and dissent differently when the issue at hand is an “internal” problem versus an issue of war or foreign relations. If there is a difference, how might it impact situations where an issue of foreign relations was reframed as a domestic conflict, as with U.S colonialism on the continent itself?

From “As Regards Patriotism,” written 1901

Patriotism is merely a religion—love of country, worship of country, devotion to the country’s flag and honor and welfare.

In absolute monarchies it is furnished from the Throne, cut and dried, to the subject; in England and America it is furnished, cut and dried, to the citizen by the politician and the newspaper.

The newspaper-and-politician-manufactured Patriot often gags in private over his dose; but he takes it, and keeps it on his stomach the best he can. Blessed are the meek.

Sometimes, in the beginning of an insane and shabby political upheaval, he is strongly moved to revolt, but he doesn’t do it—he knows better. He knows that his maker would find out—the maker of his Patriotism, the windy and incoherent six-dollar sub-editor of his village newspaper—and would bray out in print and call him a Traitor. And how dreadful that would be. It makes him tuck his tail between his legs and shiver. We all know—the reader knows it quite well—that two or three years ago nine-tenths of the human tails in England and America performed just that act. Which is to say, nine-tenths of the Patriots in England and America turned Traitor to keep from being called Traitor. Isn’t it true? You know it to be true. Isn’t it curious?

Yet it was not a thing to be very seriously ashamed of. A man can seldom—very, very seldom—fight a winning fight against his training; the odds are too heavy.

Read the current Sam’s Shorts selection