Welcome to Sam’s Shorts! Each month we bring you a brief passage from one of Mark Twain’s less-familiar works, inviting you to read, reflect, and respond. Then we share what we learned from your responses, answer some of your questions, and tell you a bit more about the background and context of the piece. You can read the current Sam’s Shorts selection here.

In December 2020’s Sam’s Shorts, we read a letter from Sam to his wife Livy dated 2 AM, Christmas Eve, 1871.

Reader reflections

A single phrase in this letter was the reader favorite by far: “that diminishing milky-way of white wings.” One reader noted that Sam seemed to really be enjoying his language in this letter–almost luxuriating in it.

Another reader noticed the interesting composition of the letter itself:

Just a general thought, but it’s interesting thinking about how atomized our communications are now, due to speed. He’s got like three/four things in this letter that don’t really “go” together and would probably not be in the same text or something today. But they’re connected here because they were contemporaneous thoughts for him. Just a general thought on how the form of letters can shape understanding, maybe.

This reader’s speculation was right: Clemens often wrote these letters to Livy before or after his speaking engagements, when he had time, and they contained all the news his fatigued mind could assemble–including his frustration with lecturing itself. Many readers had read part of this letter before–the Christmas part–but not the ending, perhaps because we’re less comfortable and familiar with this style of communication. The timing of the communication itself made some readers feel kinship with Clemens: “Sam and I seem to share a habit of working late, staying up late, and/or insomnia. I often think about the peace of the night when I can’t sleep.”

Where does this piece fit in Twain’s personal and professional life?

Many readers wondered if it was common for Sam to be away from his family at Christmas, especially for this purpose. During this period of his life, lecture tours were a particularly important part of building his brand, so to speak. They brought in money, certainly, but they also functioned as promotional tours for his books. This letter was written in the middle of his longest tour to date: October 16, 1871 through February 27, 1872, with 77 speaking engagements throughout the Midwest and the Northeast.

But even before Sam was a famous speaker, it wasn’t uncommon for him to be apart from his family at Christmas. For instance, he wrote a Christmas Eve letter in 1853 from Philadelphia where he was working in the printing industry, having just turned eighteen the month before.

Many commented on how difficult it must have been for him to be away from his family at Christmas, warming himself with the Christmas legend, perhaps even imagining that Livy and Langdon were looking up at the same stars on Christmas night. Spare a thought, too, for Livy. She was not only without her husband on Christmas, she was also caring for a 13-month-old while six months pregnant with their second child!

“Mine takes splendidly–right arm sore”

Folks had a lot of questions about the historical context of this letter:

- How was the smallpox inoculation delivered during this period?

- What were the specific rationales for instituting fines for not being vaccinated?

- What populations or groups were not vaccinating and for what reasons?

- Was lack of vaccination particularly a problem in Chicago?

Quite a few readers also wondered about Clemens’ own perspective on the vaccine, and some assumed he was being glib about the recommendations of the government and/or medical professionals when he stated: “the theory is, keep doing it—for if it takes it shows you needed it—& if it don’t take it is proof that you did not need it—but the only safety is to apply the test, once a year.”

Perhaps the most important bit of context to know for understanding Sam’s letter is that of all the deadly diseases that people in the 19th century faced, smallpox was the only one they could protect themselves against in this way–medical prevention, rather than just public health measures.

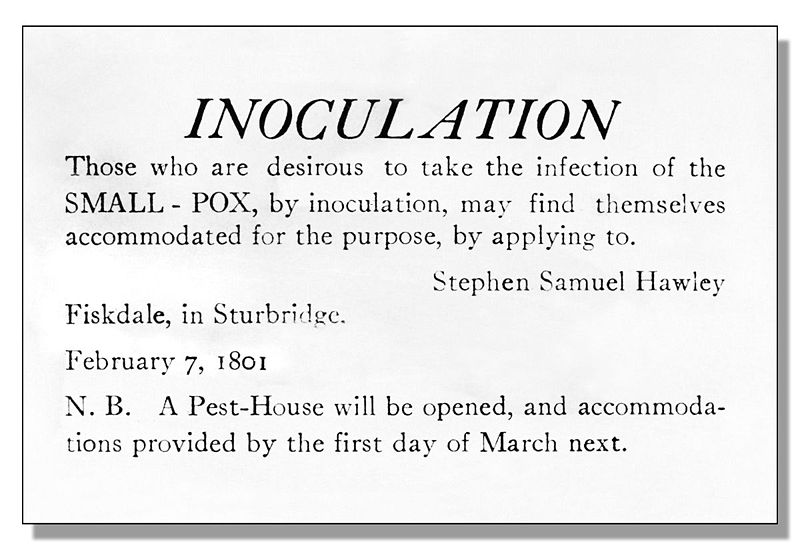

Some form of immune system-based protection against smallpox had been around for more than 60 years at this point, and was widely practiced both in the U.S. and around the world. The earliest form dates to around 1000 BCE. Known as variolation in English, named for smallpox’s Latin name Variola major, this practice flourished in China, India, the Ottoman Empire, and parts of Africa before being adopted by Europeans in the 18th century. In one approach, dried and ground smallpox scabs were blown into the nostrils, while in other places pus from smallpox pustules was introduced into a small incision in the skin. Massachusetts minister Cotton Mather learned of inoculation from an African man he held in slavery, and became a fierce advocate of the practice, which was used in Boston’s 1721 smallpox epidemic.

Though it was widely adopted, it wasn’t without controversy–or risk. Inoculation wasn’t accepted everywhere in British North America–Thomas Jefferson had to travel from Virginia to Philadelphia to be inoculated, and he ended up defending a doctor whose house had been burned by anti-inoculation rioters. There was some danger in inoculation. It introduced live smallpox virus into the body to prompt an immune reaction, and 1-2% of those inoculated in this way died from the smallpox infection they received. Still, compared to the 30% death rate from smallpox itself, and the horrific side effects that survivors endured, many people thought it was worth it. The increased prevalence of smallpox in Virginia in 1776 prompted Jefferson to urge his wife to travel to Philadelphia to be inoculated.

It was Edward Jenner’s late 18th century innovation of using a related disease, cowpox, to prompt an effective but less dangerous immune response that gave us vaccination–drawn from vacca, the Latin word for cow. To vaccinate an individual, practitioners dipped a clean lancet into fluid taken from a human cowpox pustule and punctured the patient’s skin to introduce the material into their system. This safer practice swiftly spread through the United States, often at the urging of federal, state, and local officials and doctors.

So why the panic over smallpox vaccination in 1871? The same movement of populations that made epidemics so dangerous also made protecting against this one so challenging. The issue wasn’t so much getting people vaccinated as it was getting people revaccinated.

The records of the Chicago Board of Health from 1867-9 give us some sense of how its members thought about public health, disease, and the progress the city had made towards preventing epidemics on the eve of Sam Clemens’ visit.

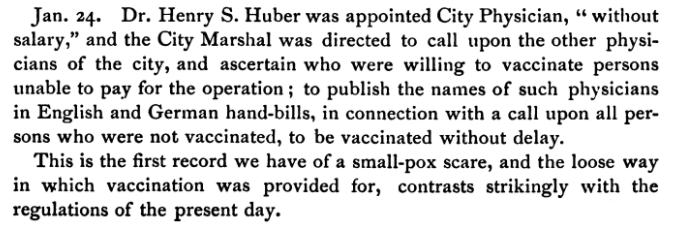

The first record white settlers had of a smallpox scare in the city was from 1848, when neighboring areas had outbreaks of the disease. The city’s response was to assemble a list of physicians who were willing to vaccinate “persons unable to pay for the operation” and to “publish the names of such physicians in English and German hand-bills” alongside a call for everyone who wasn’t vaccinated to get vaccinated right away. Twenty doctors agreed to provide these vaccinations for free.

This expansion of public health targeting smallpox was actually a response to an outbreak of a different disease. The cholera epidemic that ravaged the city in the 1840s left one out of every thirty-six city residents dead, and led to changes to public health and sanitation that lasted well after that particular cholera outbreak had abated.

The city took action on smallpox not only because of the danger it presented to the entire population, rich or poor, native-born or immigrant, but because it was the only infectious disease for which there was a well-known and accepted preventative treatment. As a result, the city moved swiftly to create systems for ensuring widespread vaccination. In 1849, the city council appropriated money to be used to vaccinate children in public schools. In 1851, the City Physician was ordered to provide the vaccination to all in the city who needed it, at the city’s expense.

Beyond making the vaccine free, the city also took enforcement steps. In 1855, the council directed the mayor to enforce an existing law requiring physicians to report cases, and public health officials were directed to place signs saying “Small-pox here” on houses with infected people. In 1860, however, “little was done by the board,” because there wasn’t much smallpox or cholera: “the duties of the board gradually became merely nominal, until its functions imperceptibly ceased.” The 1867-9 records show the current board members were concerned about this, and had attempted to raise the rates of vaccination and revaccination.

The focus on revaccination was rooted in two concerns. First, local health officials were unsure how long the vaccine’s protection lasted, and so they urged revaccination–similar to what we call a “booster shot” today. But doctors were also worried about variants, that perhaps the vaccination a person had received in Chicago two years prior, or in Manchester or Dublin or Munich before they immigrated, wouldn’t protect against the current epidemic. This is what Sam seems to have been thinking of when he talked about how the advice was to get the vaccine, and if it “took”–if it prompted an immune response–it showed you had needed it.

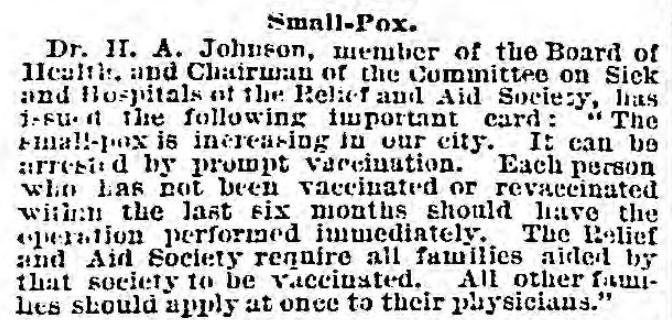

In December 1871, when Clemens was in Chicago, we see the positive and negative results of these approaches to public health. The city had the capacity to ramp up vaccination quickly using these previously established networks and resources, but it becomes clear that both regular vaccination and revaccination continued to lag.

These passages, along with the longer history of Chicago’s board, demonstrate a familiar pattern in American public health systems–who they can urge, who they can plead with, who they can incentivize, and who they can compel. While the city appropriated money for free vaccinations, it was only able to compel certain groups to be vaccinated–those who were seen as dependent by virtue of their age or social standing. While we may be familiar with requirements for children attending public school to be vaccinated, it’s important to note that vaccination was a condition placed on poorer Chicago adults if they wanted to receive financial support from the Relief and Aid Society–a private organization that received appropriations from the city. There’s a striking similarity between the people who could be compelled to take a vaccine and the people who were often used as test subjects during the development of these practices.

Despite Sam’s warning to Livy, there doesn’t seem to have been a $25 fee for not getting vaccinated in Chicago at this time. In fact, nearly a month after his visit, some city doctors were again urging leaders to make the vaccine compulsory, though no proposed punishment was listed. They gestured to the extremely low rates of infection in public schools as proof that mass vaccination was worth it.

It’s not surprising that Sam was confused about this fine, however. As we’ve seen, it’s easy for misinformation to flourish in times of epidemic disease. One issue of the Tribune during his stay earnestly recounted the story of a woman who was sure she’d gotten smallpox from a distant friend’s letter.

But what wasn’t confusing to most in the United States, whether laypeople or medical professionals, was the fact that the smallpox vaccine worked, and that smallpox was the only major deadly disease that could be vaccinated against. It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that Sam Clemens–away from his family on Christmas–should fervently urge his wife to protect herself any way she could. Their infant son Langdon–”our boy”– was especially susceptible to illness as an infant, and so his parents’ vaccinations would protect him as well. Sadly, six months after this letter, Langdon died of diphtheria, a disease which killed millions of children around the world at the time. There wouldn’t be a vaccine to protect children from diphtheria for another fifty years.

Letter from Sam Clemens to Livy Clemens, 1871

Chicago, Christmas, 2 AM

Joy, & peace be with you & about you, & the benediction of God rest upon you this day!

It must have been about this hour, when a brooding stillness lies like a healing sleep upon all nature, & the passions are intranced in human hearts & the good impulses take holiday & visit with the gentle strangers that come in dreams from some happy country beyond our ken, that marvelous vision, that diminishing milky-way of white wings, stretched its long course out of the firmament & from the heights of Bethlehem the angels sang Peace on Earth, good will to men!

There is something so beautiful about all that old hallowed Christmas legend! It mellows a body—it warms the torpid kindnesses & charities into life. And so I hail my darling with a great big, whole-hearted Christmas blessing—God be & abide with her evermore!—Amen. And God bless the boy, too—our boy.

And now to bed—for I have worked hard all day yesterday—& till late last night—& all day again & till now—on my lecture—& it is re-written—& is much more satisfactory. To-morrow I shall memorize it.

Get vaccinated—right away—no matter if you were vaccinated 6 months ago—the theory is, keep doing it—for if it takes it shows you needed it—& if it don’t take it is proof that you did not need it—but the only safety is to apply the test, once a year. Small pox is everywhere—doctors think it will become an epidemic. Here it is $25 fine if you are not vaccinated within the next 10 days. Mine takes splendidly—arm right sore. Attend to this, my child.

With a whole world of love & kisses.

Sam’ℓ

This letter can be found in the University of California’s Mark Twain Project Online.