Icons Abroad: Samuel Clemens and Frederick Church in the Holy Land and in their Homes

Icons Abroad: Samuel Clemens and Frederick Church in the Holy Land and in their Homes

By Paige Moreau, Curatorial Department Intern 2018

The first time I visited the Mark Twain House I was in high school; this summer I returned for an internship in the Curatorial Department as a budding graduate student and neophyte art historian. Although I have changed in the eight or so years since my first visit, my sense of wonder each time I step into the house has not. One room in particular continues to enthrall me: the foyer. I remember my first visit, stepping out of the thick air and sunlight of a July day, crossing the threshold of the house, and feeling mesmerized by the visual feast before me. I felt dizzied by the opalescent flecks of stenciled paint that danced across the dark wood and puzzled by the seemingly foreign objects sprinkled across the room. My reaction upon touring the house again at the start of my internship was much the same, but this time I needed to know more. I knew that the Clemenses had hired Edward Tuckerman Potter as the architect of the home and that in 1881 they had Louis Comfort Tiffany and Associated Artists come embellish the interior. Nevertheless, as an art historian, I longed to know where the inspiration for this dazzling room came from. Between casually researching my interest in the foyer and my daily tasks as an intern, I came across a fascinating connection between Mark Twain and Hudson River School artist Frederic Church that would leave me with a deeper understanding of Clemens’ home.

One of the projects I had my hands in during my internship was cataloguing the museum’s collection of letters to and from the Clemenses. I was excited to find some correspondence between Mark Twain and Frederic Church; that sparked my interest in researching their relationship. To my dismay, they spent little time together. Aside from a short trip Sam took in 1887 to visit Church’s estate Olana in Hudson, New York and a few letters back and forth. This lack of personal connection did little to set me back; I was hooked on Church and as I continued my research, I uncovered a correlation between the lives of the two men independent of their cordial but altogether unfamiliar relationship.

1867 was a formative time in the lives of Samuel Clemens and Frederic Church. The men separately and at different stages in their lives embarked on a pilgrimage to the Near East. Travel, in the lives of the two men, would come to influence their work, their global perspectives, and importantly, the construction and design of their respective homes. At the time, the 40-year-old Church was well beyond his years in experience. A successful painter and businessperson, he had gained notoriety for the success of his paintings Niagara and Heart of the Andes. Church had known great loss at his young age, experiencing the death of his first two children in 1865 to diphtheria and the death of his sister shortly after. As a religious man, Church’s travels abroad were largely inspired by a personal search for healing and spiritual connection. The sociopolitical climate of the past decade, including the end of the Civil War and the release of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, along with his personal misfortunes, weighed on Church, affecting his paintings and his faith. The uncertainty of the time inspired him to “seek, perhaps, some confirmation of the essential truths of life.”

Conversely, Samuel Clemens was a 31-year-old single travel writer, who had only recently adopted the pseudonym Mark Twain. After the relative success of his publication “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog” in the New York Evening Press, Clemens was drawn east to work on an assignment for the Alta California newspaper out of San Francisco. In June of 1867, he boarded the Quaker City steamboat in New York and headed for the Holy Land, a trip that would introduce him to his future brother-in-law and supply the foundation of his book The Innocents Abroad.

I began wondering how the travels of these two men came to influence the architecture of their homes. For Frederic Church, the answer is straightforward: his estate Olana is an amalgam of eastern inspiration. Through evidence found in building records and journal entries, Church clearly had a vision for his home inspired by the Near East and had a heavy hand in controlling the details of construction and decoration. Clemens, on the other hand, was more relaxed about the particulars, leaving for an extended vacation in England after seeing only preliminary drawings for the house from architect Edward Tuckerman Potter.

Frederic Church’s home, Olana, sits atop a hill on 250 acres overlooking the Hudson River. The estate is a shining example of Church’s ability to meld together styles and perspectives in imaginative ways. Olana exudes eclecticism, resembling the grandeur of an Italian villa, decorated with Persian design elements both true to form and of Church’s imagination, and functions as a frame for vistas of the Hudson Valley. While Church was traveling through the Levant, he used Beirut as a home base. His time in the city allowed him to familiarize himself with the local architecture. He compiled a mental bank of design elements for use on his own home. Upon his return to New York, design of the home came under way, and Church kept close watch on the project to ensure that the finished product fit his lofty vision. The builders and architects Church employed had never encountered Persian architecture and maintained different, occidental, notion of great design. Church, in his own opinion, was the only one that could adequately translate his vision into reality. He became obsessed with studying Persian and oriental architecture making color swatches for rooms, designing stencils, and sketching mock-ups for decorative elements. What resulted from Church’s dedication and careful planning was a work of art that molded together the great loves of his life: the vistas of the Hudson and the dwellings of the East.

Unlike Church, Samuel Clemens’ travels loosely inspired his house in Hartford, Connecticut. Inspiration for the house pulls more generally from the Victorian spirit of travel. Clemens’ trip to the Holy Land aboard the Quaker City steamboat, often considered America’s first cruise ship, was one of the first meant for leisure travel. This newfound passion for travel marked the rooms of the house with vaguely internationally-inspired themes. Known for having expressed interest in foreign, often Eastern, cultures and imagery, the artists and artisans employed to decorate the Clemenses’ house had their hand in championing the Aesthetic Movement. Lockwood de Forest, who designed the carved teakwood paneling around the fireplace, produced paintings and furniture inspired by images of northern Africa, the Middle East, and India. Louis Comfort Tiffany, whose Associated Artists were responsible for the foyer stenciling, produced water-color paintings of Algerian markets. In line with the Aesthetic Movement, these artists were attempting to capture beauty in objects rather than evoking deeper meaning. This stress on beauty and art for art’s sake aligns with the Clemenses’ detached interest in the design of the house. They hired Potter to plan the house and entrusted that it would be beautiful.

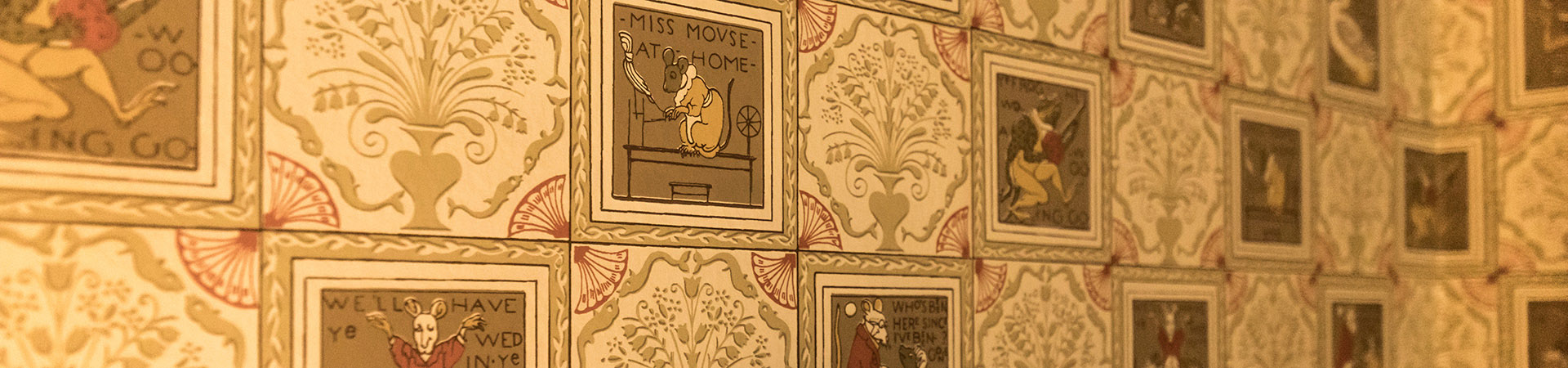

For the foyer, Louis Comfort Tiffany’s intricate oriental stencil work decorates Edward Tuckerman Potter’s French gothic inspired ceiling moldings, marrying East and West in a geometric dance. While the Clemens family lived in the house, objects acquired by them on subsequent travels decorated the foyer and the rest of the house. A selection of objects suggesting a connection to Clemens’ travel in the Near East currently ornament the foyer. A painting by Lockwood de Forest, Arab Café, Cairo, hangs on the far wall of the room. The painting depicts a group of men in traditional dress gathered around an outdoor café. The dark colors of the men’s skin and dress against the washed out tans of their surroundings suggest a voyeuristic curiosity of foreign people. The fireplace is flanked by two shadow boxes, one containing miniatures of Persian sultans and the other containing a replica of an archway from the Alhambra. Additionally, a lantern, donned with the Islamic crescent, hangs from the center of the room. These accoutrements have the capability of transporting any visitor to a location half a world awa, but they also have the power to convey a message about the American Victorian era, one that suggests an adoration of beauty no matter where it is found.

The correlations I found between Church and Clemens helped me to unlock some answers about the foyer of the Mark Twain House while also giving me a glimpse of Samuel Clemens’ personality. For all of Church’s seriousness and intention in designing and decorating his home, Clemens’ approach was more lighthearted. The two men, in my opinion, represent opposing sensibilities and relationships to the culture of the time a dissonance could explain their lack of a real relationship.

References:

Avery, Kevin J., and Frederick Edwin Church. Treasures from Olana: Landscapes by Frederick

Edwin Church; Cornell Univ. Press, 2005.

Courtney, Steve, and Hal Holbrook. The Loveliest Home That Ever Was: the Story of the Mark

Twain House in Hartford. Dover Publications., 2011.

Dequelin, Rene. “A Many-Sided Creator of the Beautiful.” Arts & Decoration, vol. 17, 1922, pp.

176-177.

Ryan, James Anthony. Frederic Church’s Olana: Architecture and Landscape as Art. Black

Dome Press Corp., 2001.